Biography of Charles Walter Stansby Williams (1886-1945)

The following biography of Charles Williams was written by G. W. S. Hopkins, in the Dictionary of National Biography, 1941-50. It is reproduced by permission of the Oxford University Press.

WILLIAMS, Charles Walter Stansby (1886-1945), author and scholar, was born in London 20 September 1886, the only son of Richard Walter Stansby Williams, clerk, of Islington, by his wife, Mary, daughter of Thomas Wall, cabinet maker, of London. He was educated at St. Albans School and at University College, London. In 1908 Williams joined the Oxford University Press as a reader, and remained a member of the staff, increasingly valued and much beloved, until his death. His duties, however, as literary adviser in a publisher’s office, although carried out with enthusiasm and wisdom, occupied a relatively small place in his life. In 1912 he published his first book of verse, The Silver Stair, and, for the next thirty-three years, wrote, lectured and conversed with a tireless and brilliant energy. In that time he produced, apart from anthologies, a number of prefaces, and a rarely interrupted series of reviews, over thirty volumes of poetry, plays, literary criticism, fiction, biography, and theological argument.

WILLIAMS, Charles Walter Stansby (1886-1945), author and scholar, was born in London 20 September 1886, the only son of Richard Walter Stansby Williams, clerk, of Islington, by his wife, Mary, daughter of Thomas Wall, cabinet maker, of London. He was educated at St. Albans School and at University College, London. In 1908 Williams joined the Oxford University Press as a reader, and remained a member of the staff, increasingly valued and much beloved, until his death. His duties, however, as literary adviser in a publisher’s office, although carried out with enthusiasm and wisdom, occupied a relatively small place in his life. In 1912 he published his first book of verse, The Silver Stair, and, for the next thirty-three years, wrote, lectured and conversed with a tireless and brilliant energy. In that time he produced, apart from anthologies, a number of prefaces, and a rarely interrupted series of reviews, over thirty volumes of poetry, plays, literary criticism, fiction, biography, and theological argument.

Williams was an unswerving and devoted member of the Church of England, with a refreshing tolerance of the scepticism of others, and a firm belief in the necessity of a “doubting Thomas” in any apostolic body. More and more in his writings he devoted himself to the propagation and elaboration of two main doctrines – romantic love, and the coinherence of all human creatures. These themes formed the substance of all his later volumes, and found their fullest expression in the novels (which he described as “psychological thrillers”), in his Arthurian poems, and in many books of literary and theological exegesis. His early verse was written in traditional form, but this he later abandoned in favour of a stressed prosody built upon a framework of loosely organized internal rhymes.

Many of Williams’s contemporaries found him difficult and obscure. Although the charge angered him, it was not altogether unjustified, for he used the word “romantic” in a sense that was highly personal and never fully defined. Its basis in his mind was Wordsworth’s “feeling intellect”, and what he chiefly meant by it was the exploratory action of the mind working on the primary impact of an emotional experience. It was his view that the romantic approach could reveal objective truth, and this conviction, at variance with the normal implication of the word, led to much misunderstanding and doubt among his readers. In order to be fully equipped for the task of following the thought of any one of his volumes, it was not only necessary to have read the majority of its fellows, but to have spent many talkative hours in his company. The art of conversation and the craft of lecturing were his two most brilliant, provocative and fruitful methods of communication. His influence on the minds of the young was salutary and inspiring, for he set his face against all vagueness of thought and pretentiousness of expression, and insisted, in all matters of literary commentary, upon a close and first-hand study of the texts. His favourite words of tutorial criticism were – “but that’s not what he says”. The honorary degree of MA bestowed upon him by the university of Oxford in 1943 was a well-deserved recognition of two successive courses of lectures which brought brilliance and a climate of intellectual excitement into the atmosphere of Oxford in war-time.

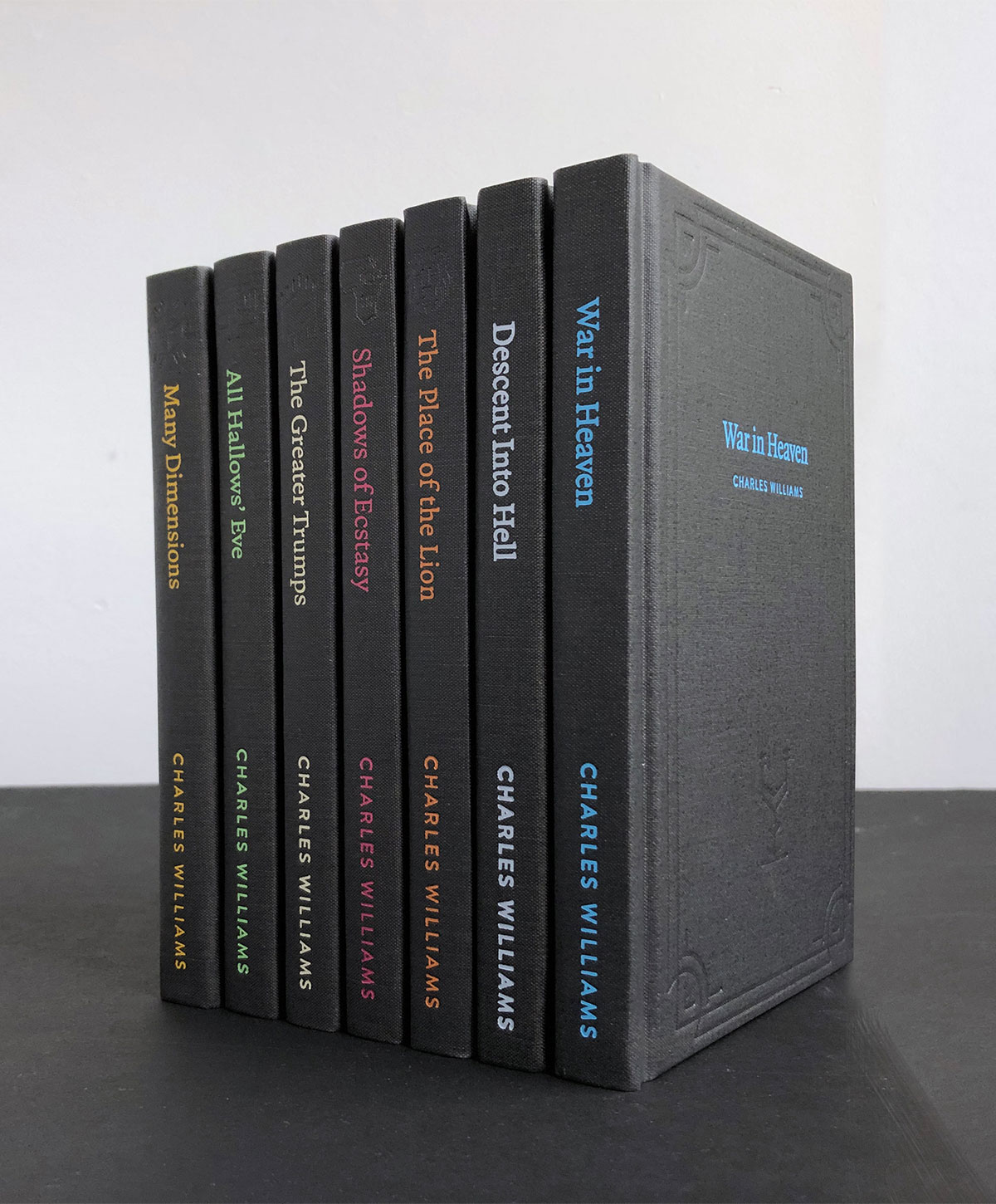

About the relative importance of Williams’s many books opinion must always differ. It is safe to say that the fullest expression of his mature views is to be found in criticism in The English Poetic Mind (1932), Reason and Beauty in the Poetic Mind (1933), and The Figure of Beatrice (1943): in poetry and drama in Taliessin through Logres (1938), The Region of the Summer Stars (1944) and Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury (the Canterbury Festival play for 1936): and in theology in He Came Down from Heaven (1938) and The Descent of the Dove (1939). Among his biographical works the most notable are Bacon (1933), James I (1934), Rochester (1935) and Queen Elizabeth (1936); and among his novels War in Heaven (1930), The Place of the Lion (1931), Many Dimensions (1931), Descent into Hell (1937) and All Hallows’ Eve (1945).

In 1917 Williams married Florence, youngest daughter of James Edward Conway, ironmonger, of St Alban’s, and had one son. He died at Oxford 15 May 1945.

[SOURCES: C. S. Lewis, Preface to Essays presented to Charles Williams (1947); private information; personal knowledge.]

Additional material:

Florence Williams died in 1970, and their son Michael in 2000. All three are buried in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford, next to St. Cross Church where Williams worshipped during the last years of his life, when the University Press office where he worked had relocated to Oxford.(During his time in London he usually worshipped at St. Silas’, Kentish Town.) Mention should also be made of his active participation in the “Inklings” during his Oxford years

Charles Williams worked nearly all his life for the Oxford University Press, also lecturing extensively on English literature for evening institutes and latterly for Oxford University. Much of his critical writing grew out of this activity. His seven novels appeared from 1930 onwards; unlike much fantasy fiction, they deal not with imaginary magical worlds but with the irruption of supernatural elements into everyday life. A legal officer has bequeathed to him the original set of Tarot cards; the investigation of a murder in a publisher’s office merges with the rediscovery of the Holy Grail; the ghost of a girl killed in an accident helps thwart a plot for world domination

His later poetry, which he considered his main work, included a number of striking plays (Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury was the next Canterbury Festival commission after Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral) and two volumes of poems on themes connected with the Arthurian cycle, Taliessin through Logres (1938) and The Region of the Summer Stars (1944) (since republished, together with earlier verses, in Arthurian Poems. edited by D. L. Dodds (1991)).

He was perhaps the most original lay theologian of the century (his chief books in this field being The Descent of the Dove, “a history of the Holy Spirit in the Church”(1939), and He Came Down From Heaven(1938)). Above all, he was passionately interested in the ways in which romantic love can be a key to understanding our relationship with God. This vision blended with his critical work in his great study of Dante, The Figure of Beatrice (1943), which inspired Dorothy L. Sayers to translate the “Divine Comedy” into English. A collection of his shorter writings, covering a wide range of his interests, was edited by Anne Ridler, with a biographical introduction, and published by the Oxford University Press in 1958 as The Image of the City. Studies of Williams have been produced by e.g. A. M. Hadfield, Glen Cavaliero, Stephen Dunning, and M. M. Shideler. A full-scale biography by Dr Grevel Lindop is in course of preparation.